Quota Attainment

Sales quota attainment is an important sales metric that shows how an individual sales rep, sales team, or sales organization performed against the quota given to them during a set time period.Continue Reading

What is Sales Capacity Planning?

Sales capacity planning is the process of identifying and forecasting the number and type of sales representatives needed to achieve a given revenue goal. Sales capacity planning is also known as sales force planning or sales capacity forecasting.

The main idea behind sales capacity planning is to use historical data to predict and plan for how you’ll generate the number of deals and the amount of revenue needed to hit your targets as a sales organization. Sales capacity planning is a crucial part of most companies’ annual sales planning process.

The main reason organizations need a sales capacity plan is to ensure they have the right number of salespeople, at the right time, in the right place with the right skills, selling their products/services in order to hit the revenue targets set before them.

It’s no longer enough to simply guess how big a team you’ll need to maintain sustainable, consistent revenue growth. Organizations must now have the math to back it up.

A sales capacity plan can also help you optimize the resources you already have on hand and keep your focus on selling more effectively rather than worrying about having a big enough team to handle increased demand.

There is a wide range of sales data that sales leaders must consider when creating a sales capacity plan. These are as follows:

In order to calculate sales capacity, you must first decide the length of your planning periods. These typically align with your goals. If you have monthly goals, plan monthly. If you have quarterly goals, plan quarterly.

Then, using your current team structure, churn rates, new hire plans, ramp times, quota, and average quota attainment to create a table or spreadsheet that shows you, for any given period, the output of your team.

While there are a variety of sales capacity models you can use, here’s a very basic formula you can start with:

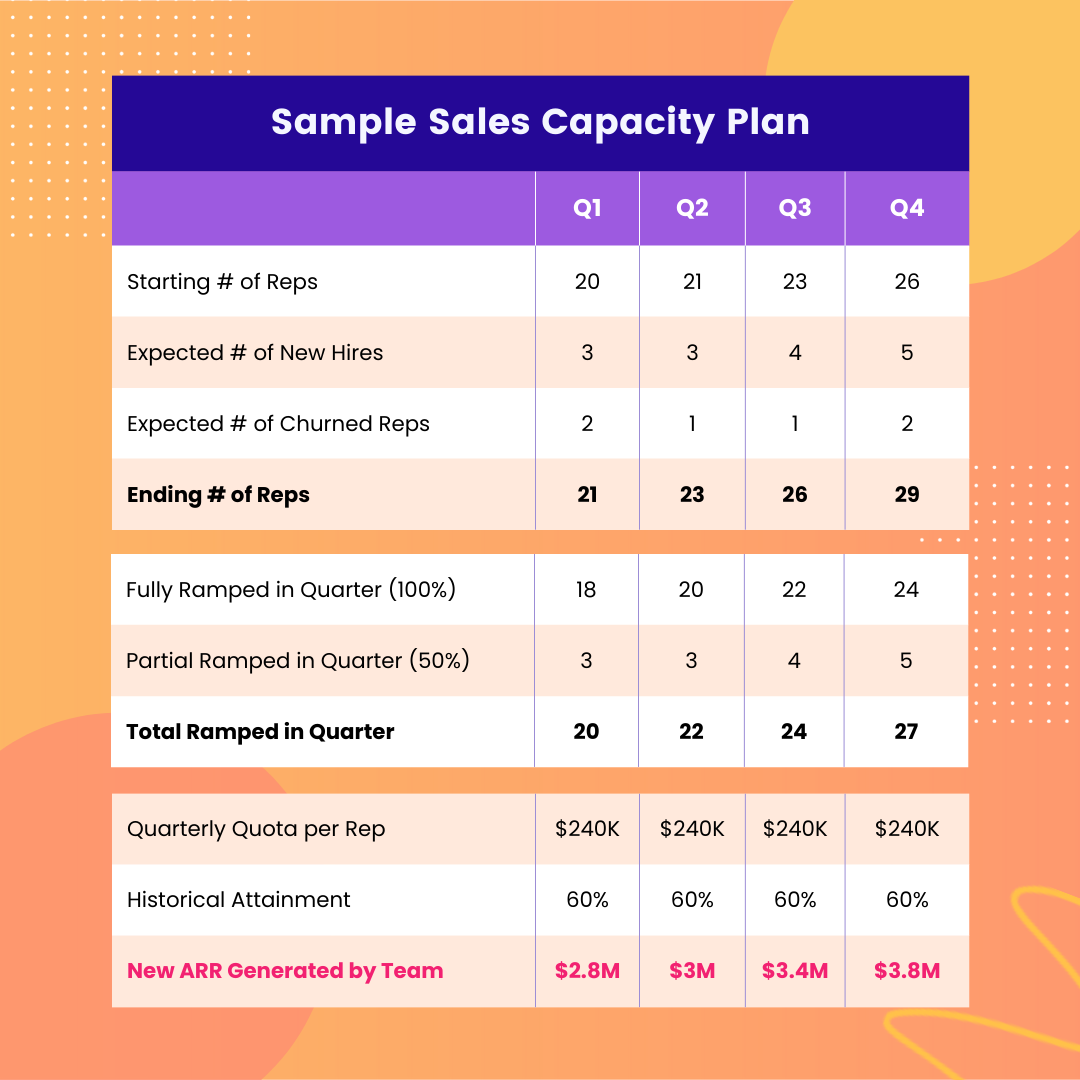

Although this formula is a good starting point, it doesn’t account for ramp times, churn, or new hire plans. To make sure your plan is as accurate as possible, we recommend mapping out the total number of reps you’re starting with each quarter, plus any new hires you plan to onboard during this period, minus the average number of reps that churn within each period.

From there you’ll want to make sure you’re taking ramp periods into account. To do this we recommend counting 100% of fully ramped reps and only 50% of new hires. For example, if you’re going into Q1 with 20 fully ramped reps, you expect to hire 2 more by end of quarter, and you typically lose 2 reps a quarter, the math would look something like this: (20 reps) + (50% of 2 ramping reps) – (2 churned reps) = Sales Capacity of 19 complete reps.

Using the final number from this most recent calculation, you can then use quota and attainment numbers to determine your sales capacity for any given time period. Here’s what that would look like mapped out over the course of a year for a standard SaaS company:

After going through the exercise above, it’s natural to wonder about how one might go about increasing the capacity of their sales team. The default assumption is that to increase sales capacity you must increase your team. But– that’s typically the final step to take.

Using the same formula outlined above, the only way to increase sales capacity is by manipulating or changing the inputs– so, increasing your reps, your quota, or improving quota attainment.

For most organizations it’s a combination of all three. We recommend you start with the less expensive levers before you resort to hiring new reps. This might include taking steps to:

If, after doing all of the above, you still need additional sales capacity, it’s time to hire new reps. But, be sure to exhaust other options first, or you run the risk of spending too much money on an ineffective team– resulting in a low ROI and ultimately hurting top line revenue growth.

Sales turnover is a major expense. Replacing a single rep costs an average of 1.5-2x their base salary, and that’s without factoring in lost revenue from reduced sales capacity while you recruit, onboard, and ramp new hires. This issue isn’t going away, either.In fact, the average annual turnover rate in B2B sales is now 35%.

Convincing your boss to sign off on more resources for sales comp can feel like an uphill battle. After all, does your organization really need to sink even more money into sales compensation? The short answer is, yes.

Watch any movie centered on sales professionals, and you’re likely to notice a recurring theme: competition. The sales reps in these films will stop at nothing to become the lone name atop a literal or figurative sales leaderboard – usually resorting to extreme tactics in order to be the best.